Our director, Albert Bonfil, was recently interviewed by psychologydegree411.com. In the interview, he discussed information about his background, as well as how he came to be a cognitive behavioral psychologist. You can read the whole interview here.

How Effective is CBT Compared to Other Treatments?

Over the last few decades, as the field of psychology has moved toward evidence-based practice, there has been some controversy about the increasing adoption of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) over other methods of treatment. Since increasing importance has been placed on treatments with research support, there has been a flood of new research available to guide clinicians and patients to the most effective treatments for psychological problems. In study after study, CBT stands out as the most effective treatment for numerous mental health issues. Furthermore, CBT treatments are usually of shorter duration, and the results are more enduring than those of other treatment methods. As a result, therapists trained in more traditional therapies, such as Freudian/psychodynamic therapists, have railed against this method of therapy because, they claim, it oversimplifies problems and aims toward a “quick fix” due to the shorter duration of treatment in CBT.

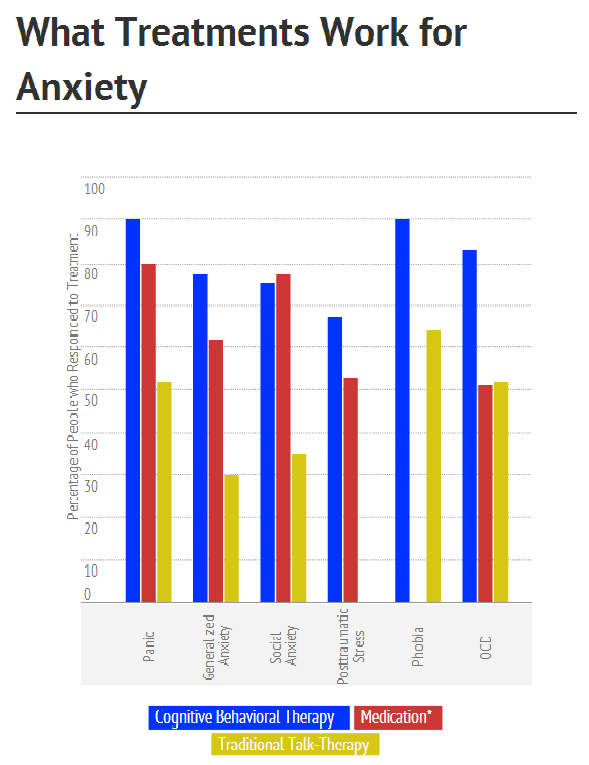

Below is a graph comparing the effectiveness of CBT with that of medication and other forms of talk therapy. Unfortunately, the research is not entirely definitive, as psychotherapy research is still in its relative infancy, not having the benefit of the bottomless pockets of big pharma. However, the initial research is striking in its implication of CBT being the treatment of choice for many psychological problems.

References:

Barlow, D.H., Gorman, J.M., Shear, M.K., & Woods, S.W. (2000). Cognitive-behavioral therapy, imipramine, or their combination for panic disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 283, 19, 2529-2536.

Bradley, R., Greene, J., Russ, E., Dutra, L., & Westen, D. (2005). A multidimensional meta-analysis of psychotherapy for PTSD. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162, 214-227.

Choy, Y., Fyer, A.J., & Lipstiz, J.D. (2007). Treatment of specific phobia in adults. Clinical Psychology Review, 27, 266-286.

Craske, M.G. & Barlow, D.H. (2008). Panic disorder and agoraphobia. In D.H. Barlow (Ed.) Clinical handbook of psychological disorders: A step-by-step treatment manual. (4th ed., pp. 1-64). New York: Guilford Press.

Eng, W., Roth, D.A., & Heimberg, R.G. (2001). Cognitive behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 15, 311-319.

Foa, E.B. & Kozak, M.J. (1997). Psychological treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder. In M.R. Mavissakalian & R.G. Prien (Eds.), Long-term treatments of anxiety disorders (pp. 285-309). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

Ladouceur, R., Dugas, M.J., Freeston, M.H., Leger, E., Gagnon, F., & Thibodeau, N. (2000). Efficacy of a cognitive-behavioral treatment for generalized anxiety disorder: Evaluation in a controlled clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 6, 957-964.

What Causes Depression: Behavioral Causes

Over 16% of Americans experience clinical depression at some point during the course of their lives. Numerous recent studies have shed light on some of the biological factors that make someone predisposed to becoming depressed. However, not everyone with these genetic markers has depression. Environmental and behavioral factors dictate whether those latencies manifest during the course of one’s life. Below is a partial list of potential behavioral causes of depression, paired with their behavioral solutions.

Not having rewarding experiences: This can take numerous forms. Sometimes, people experience a significant loss, such as the loss of a loved one or losing a valued role at work. Without replacing the old source of reward with something new, people are significantly more likely to become depressed. Loss of reward can also take the form of not engaging in many rewarding activities. By not having enjoyable hobbies, going out with friends, or engaging in work that one finds meaningful, it is difficult to maintain an upbeat mood. Finally, not engaging in self-reward, such as praising oneself or treating oneself for a job well done, also falls into this category. The solution for all of these causes is to gradually and consistently increase behaviors that have the potential for reward. On the surface, this may seem like an easy fix, but it can be hard to find the motivation to expend energy when you are depressed. Luckily, a cognitive behavioral treatment is designed expressly for this purpose, called behavioral activation.

Not using problem-solving skills: When you encounter problems you feel you’re helpless to solve, you may be more vulnerable to depression. The more passive you become in the face of problems, the less likely it is that they will get solved. If your habit is to feel problems are hopeless and not do anything to solve them, you will end up leading a life in which you very seldom get what you want. The remedy is to change your orientation to problems, from being the victim of problems to being the solver of problems. If something doesn’t go right at work, brainstorm solutions and commit to one. If you don’t appreciate how someone treats you, assertively let them know and ask for what you want. If you don’t know the answer to a question, research the answer. Confronting difficult situations head-on with solutions is generally a more effective way of coping with them.

Changing Circumstances: The one thing that is constant in life is change. Big life changes, such as moving to a new city or becoming a parent, can require new learning and can sometimes make people feel unprepared or ill-equipped to handle life. One way to address this is to approach changes with some degree of acceptance, letting go of expectations. Turning the mind toward acceptance can help us be more willing to experience less-than-ideal circumstances and make the best of a difficult situation, using it as an opportunity to grow.

Feeling helpless: If you are in a situation in which you feel no matter what you do, you get the same unrewarding experiences, you may be more vulnerable to depression. People who feel this way often give up after a while, determining no matter what they do, they are powerless to change things for the better. If this is the case, it may be helpful to think about things differently. Bounce the situation off a few friends, and allow yourself to brainstorm all kinds of solutions, even those you couldn’t see yourself doing. Afterward, you may have a different perspective on how to fix things. Sometimes, very rarely, no matter how valiant our efforts are, some environments are just intransigent. In those cases, after you’ve exhausted every other strategy, it may be best to cut ties with that environment and find one that is more yielding.

Passivity: If you are not in the habit of asking for what you want, you are probably not in the habit of getting what you want. The less you get what you want, the less reason you have to feel happy. People are usually passive because they fear some negative consequence of speaking up. Usually, upon investigation, these negative consequences are unlikely and are more emotion-driven assumptions than facts. Many people are worried that if they are assertive with someone, that person will become angry or think less of them. The way to be more assertive if you are worried your relationship with the other person may be at risk is to examine these assumptions and determine how likely they are. Examining our thoughts somewhat objectively can be a very difficult task and requires the help of a trained cognitive therapist. Click here for more information on cognitive therapy for depression.

Several behavioral causes of depression exist and have clinically researched and tested cognitive-behavioral remedies. Depression is a serious psychological problem. If you find yourself experiencing symptoms of depression, it is not recommended you go it alone by trying these techniques yourself, but seek the help of a trained cognitive behavioral psychologist. Cognitive behavioral therapy for depression is usually significantly shorter than traditional talk therapy, lasting only 12-20 sessions, and significantly more effective. Click here for more information about cognitive behavioral therapy.

All material provided on this website is for informational purposes only. Direct consultation with a qualified provider should be sought for any specific questions or problems. Use of this website in no way constitutes professional service or advice.

Acceptance Techniques to Reduce Anxiety and Worry

People who have difficulty controlling their anxiety generally worry a lot about a lot of things. This is known as generalized anxiety. One factor that often fuels generalized anxiety is difficulty accepting the absence of certainty. For most people, uncertainty about important areas of life is unpleasant. It may seem as though life would be easier if you knew how everything would turn out in advance. Unfortunately, this is not a realistic expectation. With life comes uncertainty. People who struggle with this often end up worrying about things they have very little control over, causing undue anxiety and stress.

A solution to fighting uncertainty… is simply accepting uncertainty. By choosing to tolerate not knowing how situations will turn out willingly, we expend less energy fighting unnecessary battles, and getting tied up in knots about things in ways that are unhelpful. Acceptance does not necessarily mean enjoying uncertainty. It merely means acknowledging that there is a degree of the unknown in everything we do and choosing not to fight this reality. Following are ways you can learn to turn your mind toward acceptance of uncertainty:

Weigh the pros and cons of accepting uncertainty: Identify the reasons fighting uncertainty feels helpful or safe, as well as the ways in which it is ineffective. Chances are the cons outweigh the pros. Being mindful of this can help you drop the struggle and embrace the unknown.

Identify areas of your life in which you’re already accepting of uncertainty: Chances are you’re already doing this, either with traffic jams along your commute, visiting a new restaurant, or meeting new people. Take a moment to consider how accepting some degree of uncertainty is helpful in these situations, and apply the same attitude with more challenging areas of your life.

Analyze what uncertainty means to you: Sometimes, we automatically associate uncertainty with a negative outcome without being aware of it. If you do this, take a step back from this thinking pattern and really identify whether there’s any evidence for this. Take another moment and identify the evidence against this assumption. Chances are, by thinking about uncertainty from this new perspective, it may seem less threatening and not necessarily negative.

Imagine what life would look like without uncertainty: Although a sense of certainty may be helpful for planning, it’s likely that too much certainty would make life pretty dull. How enjoyable would movies be if you knew exactly what was going to happen every step of the way? And with absolute certainty, there would be no pleasant surprises. Envisioning what would happen if we really got our wish and everything was more certain may cause us to think twice and consider that uncertainty comes with some benefits we normally overlook.

The next time you tense up when you encounter a feeling of uncertainty, bring to mind these different ways of relating to the situation and see what happens. You may find that you can more calmly handle whatever it is that’s on your plate, and you may just be able to appreciate some of the benefits of uncertainty.

This technique for reducing anxiety comes from a cognitive behavioral treatment for anxiety disorders that has been shown to be effective in significantly reducing symptoms of anxiety in 70-80% of patients (Durham, 1995). Compare that to traditional talk therapy, which helps about 30% of patients with generalized anxiety and takes twice as long. Click here for more information about cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders.

Durham, R.C. (1995). Comparing treatments for generalized anxiety disorder: Reply. British Journal of Psychiatry, 166, 266-267.

All material provided on this website is for informational purposes only. Direct consultation of a qualified provider should be sought for any specific questions or problems. Use of this website in no way constitutes professional service or advice.

Control Your Worrying with Constructive Worry vs. Unconstructive Worry

People who worry often believe their worrying helps them avoid the things they worry about. Worrying can feel as though it is helpful in preparation, problem-solving, or securing a level of certainty or predictability. The reality is that worry can be helpful sometimes, but when worry becomes difficult to control and results in persistent anxiety, it is no longer helpful. Determining whether your worry is productive or unproductive can help you decide whether to use the worry to your benefit, or to let it go.

There are several ways of determining that your worry is productive:

There is a solution to your problem: Worrying can aid problem-solving by helping you focus on figuring something out. For instance, if you know a road will be closed tomorrow, and you have an important meeting to get to, worrying can be helpful in prompting you to find an alternate route and leave a little earlier to ensure you’re not late. That’s a solution. Unproductive worry has no solution. It is just going over the problem again and again, increasing tension and anxiety. For instance, fretting about making it to the meeting on time without any plan of doing so, or figuring out the plan but continuing to worry is unproductive.

The worry is limited to one situation: Effective planning and preparation can really only be done by focusing on one thing at a time. If you find your mind jumping from situation to situation, it is unlikely that any effective solution will come from this. In fact, you’ll probably end up feeling overwhelmed. Similar to this is the tendency to get caught up in a chain reaction of events: “If this goes wrong, then this will go wrong, then that will go wrong…” Again, what is lacking is focus on one event.

Worrying lasts less than 10 minutes: If you have been focusing on something for more than 10 minutes, planning is not happening. Instead, you’re probably just ruminating or obsessing. Limiting your worry to 10 minutes can be helpful in increasing the pressure to come up with a solution. Sometimes, prolonged worrying is the result of not being able to find a perfect solution. The 10-minute time limit can also help you be more willing to accept an imperfect solution. When you think about it, an okay solution is better than no solution at all.

You acknowledge there are factors outside of your control: If your worrying is focused on things over which you have no control, there is no planning happening. In fact, you could worry about the same thing constantly for years without being any more prepared or any closer to a solution. Productive worry involves taking into account that you may have influence over certain situations but not control. Focus on ways you can influence and give up the fantasy of control.

Anxiety does not dictate your worry: Some people feel worrying has achieved its purpose once their anxiety dissipates. Unfortunately, usually, the more you worry, the more anxiety you feel. Additionally, there are some things that will always elicit some level of anxiety within us. Anxiety presents itself because we care about something. The things we care most about are the biggest triggers of anxiety. Sometimes, you may worry about something, problem-solve it, and identify a plan, but still feel some unease about the situation. This is okay and doesn’t necessarily mean you need to worry about it more. What it means is there is something important about this situation. Doing what matters sometimes stirs up unpleasant feelings.

Once you’ve determined whether your worry is unproductive worry or productive worry, you can either use it to prepare or let it go. This technique is part of a cognitive behavioral therapy protocol for generalized anxiety that has been shown to be effective in significantly reducing anxiety in 70-80% of patients, as compared to the 30% of patients who receive traditional talk therapy (Durham, 1995). Click here for more about cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety.

Durham, R.C. (1995). Comparing treatments for generalized anxiety disorder: Reply. British Journal of Psychiatry, 166, 266-267.

All material provided on this website is for informational purposes only. Direct consultation with a qualified provider should be sought for any specific questions or problems. Use of this website in no way constitutes professional service or advice.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Pie Chart Technique II

In a previous article, I outlined a technique in which you can use a pie chart to make a decision about how to act when you feel overwhelmed. Another cognitive therapy use of the pie chart is to, in graphic form, re-examine how you think about things. Writing our thoughts down can be a helpful tool to gain perspective, and creating a visual representation can be even more effective in impacting our unhelpful thought patterns.

This article will focus on how to use the pie technique to reevaluate how we make sense of situations that don’t go the way we want. This technique is especially useful in helping us rethink things we unfairly blame ourselves for.

Step 1: Identify the automatic thought that comes to your mind when you are being hard on yourself for something going wrong. For instance, if you get a bad grade on a test, you might have the thought, “I failed because I’m stupid.”

Step 2: Come up with a list of alternative explanations – as many as you can think of. These need not be mutually exclusive explanations. In most cases, all of them probably played some part in the outcome. For the example above, your list may include things like:

The test was difficult.

I missed several classes.

I studied the wrong material.

The teacher rushed through the material.

Bad luck.

Step 3: Assign a percentage to each explanation. The percentage should reflect the degree to which each explanation contributed to the situation. For instance, the explanation “I missed several classes” might receive a 50% if a large portion of the test was on material covered during the missed classes. However, if the classes missed were not especially important, you might assign them less importance, like 15%. After reviewing the alternative explanations list, assign a percentage to your original automatic thought. Add up the percentages to make sure they add up to 100%. If they don’t, reassign the percentages until they do.

Step 4. Finally, use the percentages to draw a pie chart. You can do this freehand or use a program like Microsoft Excel to do this quickly.

Now that you’ve spent time seriously considering alternative explanations, you’ll likely put a little less stock in the original automatic thought. The less you believe the unhelpful appraisal, the more you’ll feel a softening of the negative emotion that goes with it. Moreover, by considering other factors implicated in the situation, you’ll probably feel more empowered to do something to solve the problem or change your behavior the next time you’re in a similar situation.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Los Angeles is a therapy practice of expert psychologists with the highest level of training and experience in providing evidence-based treatment. Click the button below to ask a question or schedule a consultation to determine whether CBT is right for you.

Using Validation to be Assertive with Difficult People

Few things are more frustrating or anxiety-provoking than having to deal with someone who is, how should I put this, a tough customer. People who are more emotionally reactive can be set off at the slightest turn of phrase despite our best efforts to be sensitive or avoid conflict. Having to deal with these kinds of people on a regular basis can be exhausting, and over time, we are often totally burned out on them to the point that we no longer have any desire to maintain any kind of relationship with them.

Validation is a skill Marsha Linehan developed (1993) to help her work with psychotherapy patients who had emotional reactivity problems. Dr. Linehan found that traditional therapy techniques were ineffective with people with hair-triggers. She determined that only by using a healthy dose of validation could her patients be receptive to cognitive behavioral therapy. Moreover, Dr. Linehan found that by relying on validation skills, she could be very direct with her patients, not feeling the need to tiptoe around sensitive topics or walk on eggshells.

Validation is ultimately about helping communicate some level of understanding of the other person is thoughts or feelings. It is not necessarily about agreement, but more about acknowledging and legitimizing at least a kernel of truth in someone’s experience. Feeling understood often has the result of reducing emotional intensity and increasing psychological flexibility. If you think of conflicts as a kind of tug of war, usually, the harder you pull causes the other person to redouble her efforts and pull harder herself. Rather than escalate to conflict, validation is a bit like dropping the rope and getting on the side of the other person. All of a sudden, there is no reason for her to continue pulling because you’re on the same side. That is how validation works.

Validation can be helpful in numerous ways (Hoffman et al., 2005). It can help to defuse anger in someone with a short fuse. Similarly, it is helpful in quickly resolving conflicts and building trust. Most importantly, it makes problem-solving and assertiveness possible with people who are ordinarily intransigent.

Following is a list of different ways to validate:

Be present: Pay attention, nod, and use eye contact. Show you are listening.

Reflect feelings: Identify her feelings, describing them without judgment. If you can, allow yourself to feel a little of the feeling yourself and communicate it with your tone of voice.

Restate the position: Summarize the other person’s perspective without judgment. Ask clarifying questions to ensure you understand the position and also to signal you care about understanding.

Normalize the other person’s thoughts and feelings: Identify how her reaction makes sense given past experience or the present context. The basic underlying meaning of this kind of validation should be “Of course!”

Match vulnerability with vulnerability: If she is being vulnerable, self-disclose your own vulnerability. The subtext with this kind of validation is “Me too!”

Using these ways of dropping the rope in the interpersonal tug of war can reduce the other person’s emotionality or rigidness and help you get your point across. You may just find that interactions with this person become less difficult or even… rewarding. If you’re (understandably) skittish and don’t want to test it out, throughout the day, notice when other people validate you. Observe how you respond. Wouldn’t it be nice if that tough customer responded the same way?

Click here for more information about how cognitive behavioral therapy might be helpful for you or someone you know.

Hoffman, P.D. et al. (2005). Family connections: A program for relatives of persons with borderline personality disorder. Family Process, 44, 2, 217-225.

Linehan, M.M. (1993). Cognitive Behavioral Therapy of Borderline Personality Disorder. New York: Guilford.

All material provided on this website is for informational purposes only. Direct consultation of a qualified provider should be sought for any specific questions or problems. Use of this website in no way constitutes professional service or advice.

Get Your Life on Track by Clarifying Values

Most of us find that we have strayed in one way or another from leading the life we want to live. This can mean a lot of different things, from spending too much time watching TV, finding we are in a career that is not fulfilling, not being the sister/husband/parent we want to be, etc. There are lots of forces that can derail us from moving toward what we value. Whatever the reason, if when you survey the landscape of your life as it is now and you find something missing, clarifying your values may be the first step in getting on the right track.

Values can be thought of as directions to move toward, rather than concrete goals. For instance, if you have the value of being a more loving spouse, there are lots of goals you can attain along the way, such as spending less time at work each week, not multitasking while spending time with your partner, and engaging in acts of kindness more frequently. Goals are important in that they can give us feedback as to whether we are moving toward values. But unlike goals, values can never be attained. We can always find new ways to move us toward doing what matters.

There is an exercise that comes out of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, in which you imagine the eulogies you might hear at your own funeral (Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 1999). This exercise is designed to help you cut through the clutter of all of the forces that serve as reasons for you to not engage in valued action and to identify what really matters to you. Give this exercise a try and see what comes up:

Imagine you’re able to watch your own funeral. Different friends and family members are eulogizing you, talking about the path you chose. Take a moment to write out a few of the things you’re afraid might be said about you if, during your life, you had backed off from what you wanted to stand for. Try this now.

Now, imagine what these people would have said had you lived your life true to your innermost values. Spending your life doing what matters rather than what was safe or easy. Take a few minutes to do this now.

This task is designed to make clear, after all is said and done, what you want to be about, how you want to live. Thinking about how you want to be remembered is one way of identifying what you want to do now. Are you making choices that are helping you be the person described in the second eulogy, or more like the person in the first one? Regardless of which eulogy is a closer fit to how you are acting in your life now, you probably have a better sense of what parts of your life are serving as obstacles to the life you want and what steps, even if they are small steps, you could take to jump into the life you want.

To make this exercise even more useful, identify one step you could take in the service of your values, and take that step today.

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K.D., & Wilson, K.G. (1999). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: An Experiential Approach to Behavioral Change. New York: Guilford.

All material provided on this website is for informational purposes only. Direct consultation with a qualified provider should be sought for any specific questions or problems. Use of this website in no way constitutes professional service or advice.

Restructure Your Thoughts by Recognizing Cognitive Distortions

The human mind is an incredibly efficient machine. Because of it, we can take in new information, store it, and synthesize it with other information to create new ideas. This complex process results in all of the marvels of human ingenuity, from the invention of the wheel to the electronic device you are using to read this article. In this way, the human mind is a kind of computer.

Like any good computer, the mind learns shortcuts over time. These shortcuts speed up the way we process information. For instance, you put a dollar in a vending machine, and it eats your money. We apply the shortcut descriptor “broken” to the machine, and we know not to put any more money in it. Shortcuts can work pretty well.

Sometimes, cognitive shortcuts actually result in less efficient information processing. If we misapply a shortcut, we end up coming away with a faulty conclusion. Take for example, the person who interviews for a job and doesn’t get it. If that person applies the wrong shortcut, she may come away from the experience thinking, “They didn’t want me, so I’ll never get a job.” It’s the same shortcut as with the vending machine, generalizing from past experience. But in this example, it’s highly ineffective and will probably result in significant emotional pain. This kind of misapplied shortcut is referred to in the cognitive therapy literature as a cognitive distortion (Beck et al., 1979).

Cognitive distortions are patterns of thinking that lead to misunderstanding and painful emotions. Below is a list of common cognitive distortions we all engage in from time to time. Read through them, and take note of the ones you are especially familiar with.

Mind Reading: Assuming you know what other people think. “He thinks I’m unintelligent.”

Personalizing: Thinking you deserve the majority of the blame for something while discounting others’ responsibility. “Because of me, we lost the game.”

Fortune Telling: Making predictions that bad things will happen without actually knowing that this is the case. “I’m going to fail the exam.”

All or Nothing Thinking: Thinking of people or situations in black-and-white terms. “If I don’t do it perfectly, then it’s horrible.”

Catastrophizing: Believing the outcome of a situation will be so terrible that you won’t be able to handle it. “If I lost this job, I’d just fall apart.”

Labeling: Assigning a one-word descriptor to the entirety of a person. “He’s a jerk.”

Overgeneralization: Assuming something based on a limited amount of experience. “I’m late to everything.”

Negative Filtering/Discounting Positives: Focusing on negatives while framing positives as unimportant. “I made an A on the test because it was easy, and besides, I failed one of the quizzes, so I maybe I’m not cut out for…”

We are all guilty of most of these from time to time. You may find that you engage in one or more of these distortions on a regular basis. If you find that to be true, the next time you are aware you are making one of these distorted shortcuts, you’ll be able to recognize it and consider a more effective perspective.

For more information about cognitive therapy techniques, read this article about cognitive reappraisal.

Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, Emery G (1979). Cognitive Therapy of Depression. New York: Guilford Press.

All material provided on this website is for informational purposes only. Direct consultation with a qualified provider should be sought for any specific questions or problems. Use of this website in no way constitutes professional service or advice.

Cure Insomnia Using Constructive Worry

If you have difficulty getting to sleep at night, one of the problems may be that your mind takes a bit too long to shut off. Long after your body has slowed down, your mind is spinning at its usual clip, oblivious to the fact that it needs to power down for the night. Often, this is because our minds are busy processing thoughts about important problems that need to be solved. Unfortunately, bedtime is not the time to solve problems. If you have made a habit out of planning, rehashing, preparing, or figuring things out when your head hits the pillow, these thoughts likely keep you up much longer than you would like, robbing you of much-needed sleep. This thinking is ultimately ineffective, and is what is called unconstructive worry.

So, is there a cure, you ask? Why yes, there is. It is the opposite of unconstructive worry, and it is aptly named constructive worry. Constructive worry involves doing all of the planning prior to, rather than during bedtime. Here’s how it goes:

1. Set aside time in the early evening (a few hours before bed) to do the planning/worrying you would normally put off until bedtime. Write down whatever problem or problem you are facing.

2. Write down the next step to get you closer to solving the problem. The next step need not be the ultimate solution to the problem, as many problems require a series of steps to come to a real resolution.

If you know how to fix the problem, write out the fix.

If you don’t know the fix and need to consult with someone or do some research, write that out.

If you realize it’s not really an important problem and you’ll handle it when it arises, write that out.

If it is an important problem with no good solution, meaning you’ll just have to accept it or cope with it, that is the next step. Write that out.

3. Put this list on your nightstand before bed. When you begin worrying at bedtime, remind yourself you’ve already dealt with your problem as best as possible. You can even tell yourself you will work on the problem again tomorrow evening if you need to, but that trying to solve problems while half asleep will probably not yield any kind of solution.

4. Turn your mind back toward sleep.

There is research that shows this technique can help to cure insomnia and may even reduce your worry during the following day.

All material provided on this website is for informational purposes only. Direct consultation with a qualified provider should be sought for any specific questions or problems. Use of this website in no way constitutes professional service or advice.