Is EMDR Therapy Evidence-Based? What the New 2025 APA Guidelines Say

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) is a widely known treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). It’s gained popularity for its unique use of eye movements to process traumatic memories. But while EMDR has helped many people, recent updates from the American Psychological Association (APA) suggest it may not be the strongest option available.

In 2025, the APA released new Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of PTSD. One major change was moving EMDR from a first-line treatment to a second-line recommendation. This doesn’t mean EMDR doesn’t work—it does for some people—but it now ranks behind other therapies that have shown more consistent results in research.

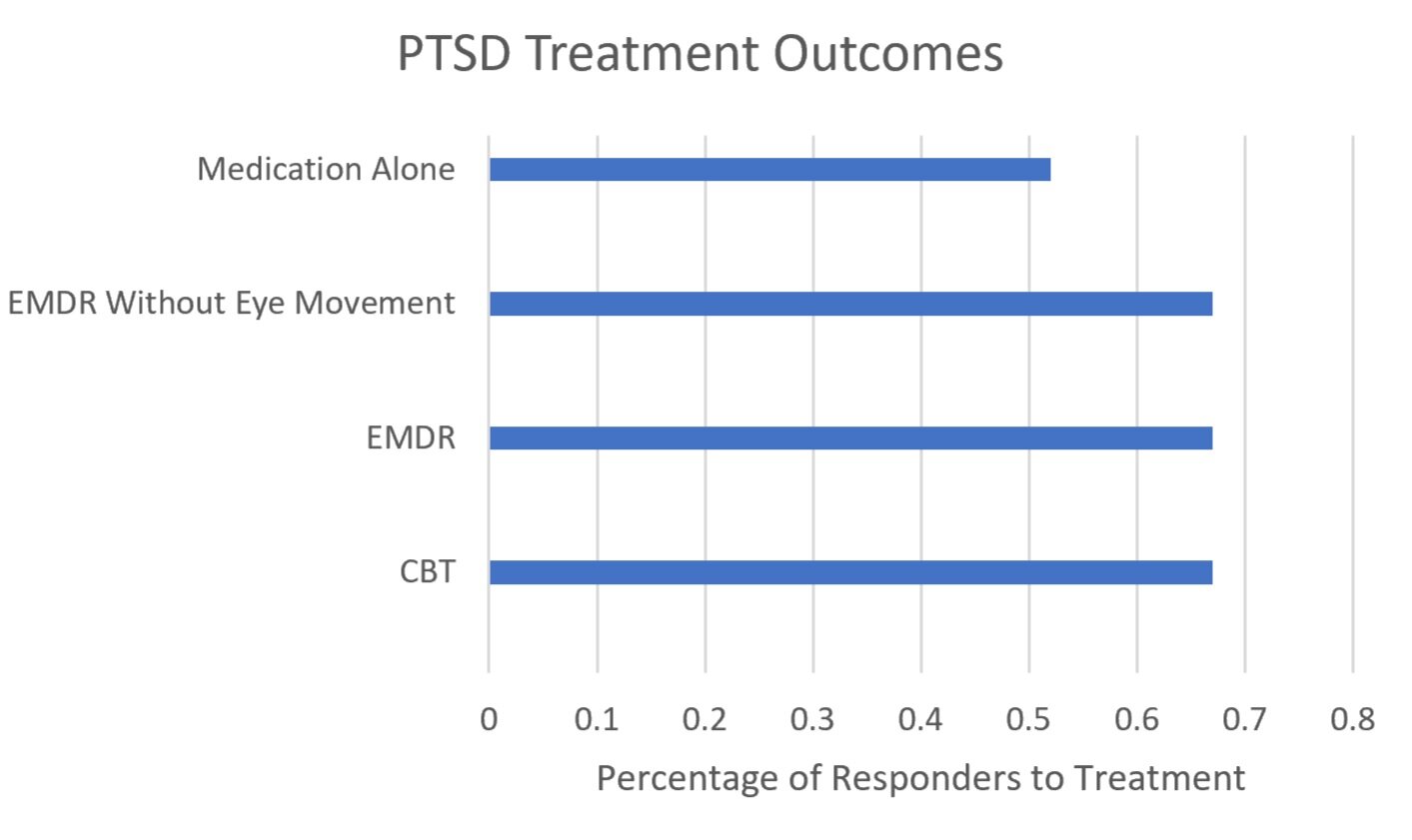

According to the APA, EMDR has been studied in many clinical trials, and the results often show moderate to large improvements. However, the outcomes vary more from study to study compared to top-tier treatments like trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), prolonged exposure (PE), and cognitive processing therapy (CPT). For certain long-term outcomes—like improved daily functioning—there’s also less solid evidence available for EMDR.

Another factor the APA considered is the emotional and logistical burden of the treatment. EMDR can be intense for some clients, and may be harder to access or stick with compared to other well-supported approaches. That’s why the APA now recommends other therapies first, especially when the goal is to choose the treatment with the best balance of effectiveness and ease of use.

In the sections below, we’ll break down what the research shows, how EMDR compares to other evidence-based therapies, and what to consider when choosing the best treatment for PTSD.

What is EMDR Therapy?

EMDR therapy is a form of therapy that emerged in the late 90’s, developed specifically to treat post-traumatic stress disorder. When it was created, it was strikingly similar to an existing cognitive behavioral treatment for PTSD called Prolonged Exposure.

Prolonged Exposure was, and still is, considered to be the gold standard treatment of PTSD. However, EMDR contained one very striking variant distinguishing it from Prolonged Exposure: The creator claimed that by shifting one’s eyes back and forth rhythmically, a neural reprocessing occurred that increased the efficacy of this treatment over existing PTSD treatments.

EMDR therapy mainly consisted of the patient repeatedly describing in detail the trauma or disturbing event responsible for their PTSD while moving their eyes side to side, following a metronome, a moving LED light, or some other object of focus. After eight phases of EMDR sessions, the patient was supposed to have less distress in response to the trauma and reduced symptoms of PTSD.

The creator of the treatment, Francine Shapiro, was not a neuroscientist, nor did she have any formal training in neuropsychology. However, she believed that the side-to-side eye movement increased insight regarding the original traumatic event by differentially stimulating both sides of the brain. Her claims about using EMDR and its effectiveness as a reprocessing therapy were very seductive to therapists looking for a more effective treatment.

Treating PTSD had been notoriously hard for clinicians without training in cognitive behavioral therapy, and the claim that it could be cured, eliminating the impact of troubling memories in as little as 12 sessions, seemed too good to be true. EMDR caught on very quickly among therapists and garnered the attention of researchers excited by the anecdotal claims of its effectiveness. However, the conclusions of numerous large-scale trials of EMDR became the subject of a great deal of controversy.

Does EMDR Work?

So, does EMDR really work? The short answer is yes… kind of. The researchers did find that EMDR was significantly more effective than placebo in reducing symptoms of PTSD, and that it was effective in reducing symptoms of most patients who completed an entire course of the therapy (Carlson et al., 1998). As a result, EMDR caught on like wildfire and was even quickly adopted by the Department of Veterans Affairs due to the promising effectiveness studies. It looked like another evidence-based treatment had been discovered, giving clinicians more options for treating people suffering from PTSD.

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing?

Davidson, P.R., & Parker, K.C.H. (2001). Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology

But there was a catch. Psychologists who had experience with the cognitive-behavioral treatment, Prolonged Exposure, recognized many of the components of the new therapy. The only difference they saw was the addition of the eye movement feature, EMDR’s defining characteristic. Following the flood of positive research, another wave of EMDR studies was published, but this time, the studies were dismantling analyses, experiments that study which parts of the treatment are most effective.

Despite the fact that EMDR had been found to be an effective treatment for PTSD when the eye movement portion was omitted from the treatment, the outcomes were similar. Several important studies (i.e., Davidson and Parker, 2001) that were conducted found the same thing: the eye movement added nothing (apart from the additional expense for the therapist) to the treatment. It was merely cognitive behavioral therapy with a dash of sci-fi pseudoscience. Furthermore, subsequent studies compared patient outcomes in EMDR with those of Prolonged Exposure and found no differences.

Should I Try EMDR?

The good news is that because the research shows that EMDR works similarly to Prolonged Exposure, it is still effective for some of the patients who receive it. The problematic piece of this is the perpetuation of this treatment despite the identification of the extra, needless components. Additionally, the treatment outcomes in different areas of quality of life are not as strong as those in first-line treatments, such as prolonged exposure and cognitive processing therapy.

The idea that the core component of bilateral stimulation or bilateral movement (via rapid eye movements) can desensitize traumatic memories lacks a robust scientific foundation. Numerous studies have led to serious psychology researchers abandoning it as an evidence-based treatment approach.

The lack of a clear and well-established theoretical framework and a consistent body of evidence has led many in the scientific and clinical communities to view EMDR with skepticism, questioning its scientific validity as compared to other evidence-based treatments for conditions like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). While some individuals may find relief through EMDR, the concerns raised by critics underscore the need for more rigorous research and evidence to support its use in the treatment of trauma-related disorders.

EMDR clearly does not incorporate the most up-to-date treatment methods, nor does it make use of the best psychological science has to offer. With the increased focus on evidence-based practice, the popularity of this outmoded therapy highlights the number of clinicians who are basing a large portion of their practice on interventions lacking strong research support. A staggering 83% of clinicians do not use exposure therapy (Zayfert et al., 2005), which is the treatment of choice for all anxiety disorders due to its high success rates. This frightening statistic underscores the importance of patients becoming informed consumers of science, asking about their therapist’s methods and training before being seen as a patient.

More troubling yet, in recent years, therapists have claimed EMDR effectively treats everything from major depression to schizophrenia. These claims are not at all supported by the research. The only treatment in which EMDR has been proven to be more effective than traditional talk therapy is PTSD. Any other claim made by EMDR practitioners is not grounded in any research or any cogent psychological science, for that matter.

So EMDR works, but not the way that it’s supposed to. This begs the question: Would you want to receive a treatment from someone who does not understand how it works?

Evidence-Based Treatments for PTSD

Prolonged Exposure Therapy: Prolonged Exposure (PE) therapy has emerged as a highly effective evidence-based treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and its success is rooted in its empirical support and therapeutic approach. PE operates on well-established psychological principles, exposing individuals to their traumatic memories in a structured and controlled manner.

This exposure helps individuals confront and process their distressing thoughts and emotions, ultimately reducing the emotional charge associated with traumatic memories. The effectiveness of PE has been substantiated through numerous clinical trials and research studies, consistently demonstrating significant reductions in PTSD symptoms and improvements in overall psychological well-being.

Furthermore, PE's adaptability to various trauma types and its structured nature make it a versatile and reliable choice for individuals who have experienced diverse traumatic events. The scientific community's overwhelming endorsement of Prolonged Exposure therapy underscores its position as a robust and evidence-based treatment for PTSD, offering hope and healing to those who have experienced trauma.

Cognitive Processing Therapy: Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT) stands as a highly effective evidence-based treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as well as for complex trauma due to its well-established theoretical framework and empirical support. CPT is grounded in cognitive-behavioral principles and targets the modification of negative thought patterns associated with traumatic experiences.

Through structured cognitive restructuring, individuals learn to identify and challenge their maladaptive beliefs, ultimately reshaping their perspectives on their traumatic memories. The extensive body of research underpinning CPT highlights its efficacy in reducing PTSD symptoms and improving overall psychological well-being.

Clinical studies consistently reveal the positive impact of CPT, making it a reliable and scientifically sound choice for individuals seeking relief from the distressing effects of trauma. Its adaptability to various trauma types and the endorsement it receives from the mental health community further solidify CPT's position as a leading evidence-based treatment for PTSD, offering hope for recovery and healing to those who have experienced traumatic events.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Los Angeles is a therapy practice of expert psychologists with the highest level of training and experience in providing evidence-based treatment for trauma and PTSD. Click the button below to ask a question or schedule a consultation to determine whether CBT is right for you.

American Psychological Association. (2024). Clinical practice guideline for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. https://www.apa.org/ptsd-guideline

Carlson, J., Chemtob, C.M., Rusnak, K., Hedlund, N.L, & Muraoka, M.Y. (1998). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR): Treatment for combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 11, 3-24.

Davidson, P.R., & Parker, K.C.H. (2001). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR): A meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69, 305-316.

Zayfert, C et al. (2005). Exposure utilization and completion of cognitive behavioral therapy for PTSD in a "real world" clinical practice. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 18, 6, 637-645.